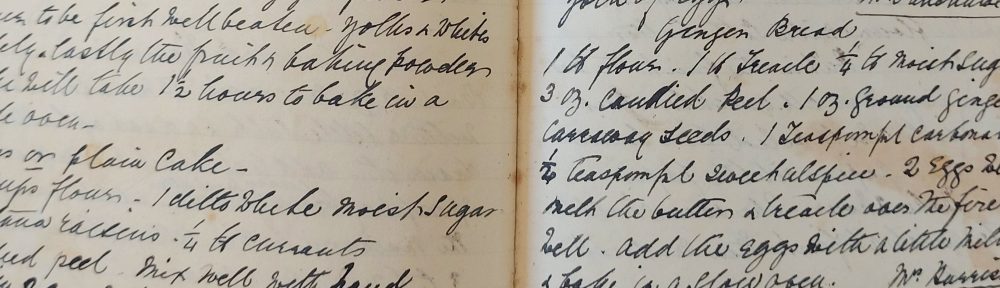

This is the first recipe in Althea’s recipe book, stuck on the opposite page to the first, proper hand-written page. Underneath it, Althea has written her name ‘Althea N. Harrison‘ and the date ‘November 20th 1866.’ On the inside cover, in faint pencil, someone (probably her husband, James, after he was widowed) has written ‘Dear Althea’s Recipe Book‘ and ‘Catherine Street. 20th November 1866.’ The recipe is a newspaper cutting, and the only recipe in the book that is not hand-written.

Althea started this book as a new bride, aged just 21. She had married James four months previously in July 1866, in Lewisham. There is no record of them living at a Catherine Street but one of the first recipes in the book is attributed to ‘M.N. L’Pool‘. James’s sister, Mary, lived in Liverpool with her actuary husband Thomas Banner Newton at 26 Catharine Street, in a wealthy area of Georgian terraced town-houses. So it seems likely that Althea spent the first few months of her marriage in Liverpool, staying with family.

This recipe though is a later addition to the book. Several northern newspapers carried the exact recipe in late 1896, which is where Althea must have seen it and thought it worthy to find space for in the book.

As with Harriet‘s recipe for Tea Cakes, the ingredients and instructions are more vague than we are used to these days. I plump for using American cups, given that they are a similar size to dainty tea-cups. I’m not entirely sure what ‘plain cake’ is (so much to learn!) but I assume it’s a basic sponge and aim for that consistency when mixing. I bake it in a medium oven for thirty minutes with really no idea of how it will turn out.

It’s certainly not gingerbread as we would understand it – hard and biscuity, crafted into the shape of men or animals. Nor does it resemble the famous crumble-topped shortbread that is Grasmere Gingerbread, which Sarah Nelson was making at the northern end of Windermere, where Althea would soon move to. This is most definitely a cake. I’m pleased by how it turns out, moist and dark. I am reminded of Jamaica Ginger Cake, which was a favourite of my father’s, although it doesn’t have such a sticky jacket.

It appears that the origins of gingerbread are neither bread nor biscuit though. The Smithsonian magazine reports that ‘In medieval England, it referred to any kind of preserved ginger (borrowing from the Old French term gingebras, which in turn came from the spice’s Latin name, zingebar.) The term became associated with ginger-flavored cakes sometime in the 15th century.’

Molasses was a new addition to my baking cupboard. A by-product of refining sugarcane or sugar beets into sugar, it has a smell and consistency all of its own; sweet but sharp and musky, almost reminiscent of engine oil. Early English gingerbread recipes featured breadcrumbs, honey and enough spices that they were viewed as much medicinal as culinary. Sugar made an appearance in the sixteenth century, followed by molasses in the seventeenth, and gingerbread changed into something resembling this recipe.

Leafing through the three recipe books, I can spot several recipes for gingerbreads, cakes and biscuits. It will be interesting to see if there are regional differences (Parkin anyone?) or if fashions change again over time.

How very fortunate you are to have access to all the historical family recipes.

LikeLike

Indeed. I feel very lucky to have them, they are such treasure!

LikeLiked by 1 person

How touching the note in the book is.

LikeLike

Isn’t it? She died from influenza in her fifties and he lived for nearly another two decades. So sad for him.

LikeLike

What an interesting page!

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike

I wonder if, like parkin, it gets stickier if you store it for a while?

LikeLike

Not sure, it didn’t last that long! I think I have parkin coming up soon, from the Yorkshire book (Harriet’s). Last time I made a version, I wasn’t impressed (like a porridgy brick) so I’ll be interested to see if this one is an improvement.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good luck!

LikeLike