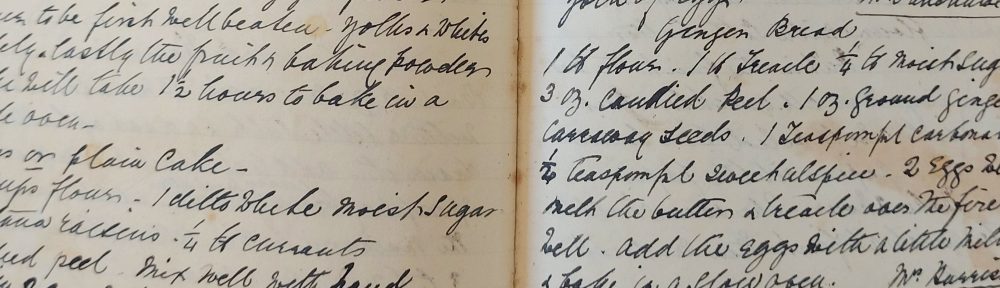

This recipe is from Althea’s book. It is not dated but sandwiched between recipes from 1880 and 1889. Confusingly, Althea’s recipes jump about in time, as if she collected them and wrote them up at a later date. I confess that I’ve skipped a couple of recipes on page three; the first because no-one in my household will eat clarified dripping in a million years, and the second because, as is often the case with Althea’s recipes, it demands more thought, preparation and purchasing than appears at first glance! That one will follow in due course.

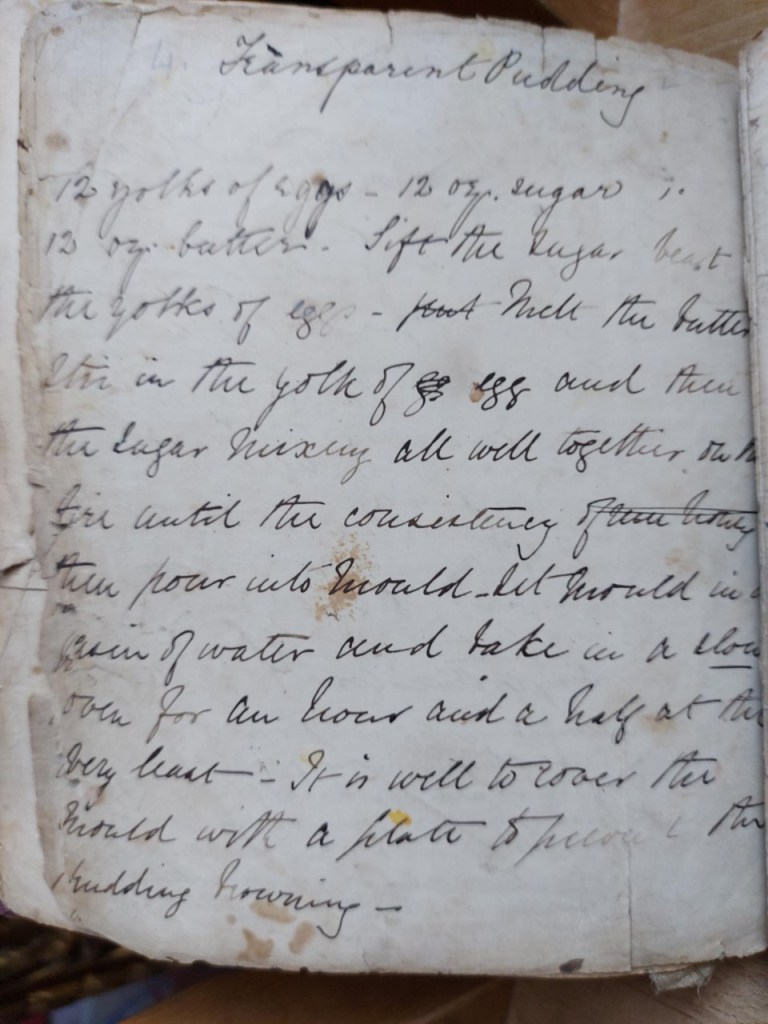

I had never heard of Transparent Pudding before:

Twelve egg yolks seemed an enormous amount and so I halved all quantities. Rightly or wrongly, I decided to ignore the advice about not letting it brown. I think I had the idea of an egg custard in my mind, one of my favourite desserts. It did make for a slightly caramelised topping, which was probably the best thing about this pudding. The inside was claggy and eggy (cleggy?) It was altogether pretty unpleasant. And certainly not transparent.

Had I mis-represented Transparent Pudding or was there a good reason it fell out of favour? It had certainly been around for a while before Althea came across it. In 1769, Elizabeth Raffald gives a recipe for it in her The Experienced English Housekeeper. In 1829 it features in A New System of Domestic Cookery formed upon Principles of Economy and Adapted to the Use of Private Families by A Lady but with the addition of some grated nutmeg, puff pastry and the potential additions of ‘candied orange and citron’. If its fortunes waned in England, it appears to have crossed over to the USA with some success; recipes for it on American websites abound, again though with the addition of puff pastry. I wonder why Althea chose to omit this part of the recipe?

At this early point in the recipe book, Althea’s marriage was still young. I can only speculate about how she came to meet James Harrison. James studied law at Trinity College, Cambridge and from 1860 was a student at Inner Temple in London. In the 1861 census, James has lodgings in Marylebone with his mother Harriett, who was a widow by this time and described as a ‘fundholder’, indicating a degree of personal wealth. Their neighbours were certainly cosmopolitan and well-to-do: a surgeon dentist from the West Indies, a French wine trader, a Greek broker. This 1862 picture from the collection of the National Portrait Gallery is likely to be James, as his sister Mary and her husband had both posed at the same studio just four months earlier. Plus, in later pictures, James has an equally strong brow game going on!

I can’t find any trace of sixteen-year-old Althea Maberly in 1861, or her mother Charlotte. Her father had died nine years earlier, so they had to leave their vicarage home in Hampshire. It appears that many of the Maberly siblings – and Althea was the youngest of twelve – made their way to southeast London. Frances is a governess in Bromley in 1861 and Marianne marries in Lewisham in the same year. Alexander is at school in nearby Kent. Henrietta marries in Blackheath in 1864 and Theresa Marcia marries in Lewisham in 1869. Mary and Catherine do not marry but both open girls’ schools in the area. Perhaps, in 1861, some of the missing family members are travelling; Charlotte was originally from Coleraine in Northern Ireland and her father lived in Dublin. Or perhaps the census record has been wrongly transcribed; the name Maberly appears in a myriad of different (wrong!) ways.

Certainly, by the time Althea married James in 1866, both were recorded as living in Lewisham. They were married at St Stephen’s Church.

cc-by-sa/2.0 – © Des Blenkinsopp – geograph.org.uk/p/2180891

There are no wedding photos and the announcement in the newspapers is concise. But I do have this spoon and fork set, labelled by someone in my family with ‘London 1866’. The engraving does not photograph well and in any case is so elaborate that it is difficult to read but it does appear that the first letter could be an ‘A’, so this could well have been a wedding gift. I only hope that if Althea ate her Transparent Pudding with it, it was better than mine…

Interesting how what is accepted unquestionably in one age is considered a health hazard in another!

LikeLiked by 1 person

The amounts of sugar alone in these recipes are a health hazard 🤣

LikeLike

My son and his family live just down the road from St. Stephen’s, which must make us cousins at least! As I read the recipe, I thought I’d probably give it a miss. Your description suggests I am entirely right not to waste 6 perfectly good eggs.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting! I’m not too far from Lewisham as the crow flies but don’t get over that way much. I must go and try and find the house Althea’s mother ended up in at some point. And yes, do not bother with Transparent Pudding.

LikeLike

I was thrilled to see that one of your ancestors was photographed by Camille Silvy! He was the most prominent photographer in London in his day. I’ve been lucky to acquire a few portraits by him. I also own a copy of this book about him. Out of curiosity, what were the names of Mary and her husband? I’d love to look them up in the Silvy daybooks at the NPG.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Ah, you spotted his style! I don’t know much about Silvy, I must admit, but gathered that he was somewhat of a society photographer in his day. Thomas Banner Newton and Mary Newton are the other relatives – they can both be tracked down via the NPG website. I’ve been looking into some of the Cumbria/Lancashire photographers of the time too, as several names crop up in the family photos…more on them to follow on later blogs, I think!

LikeLiked by 2 people

The portraits of Thomas and Mary are both very fine. Silvy had a wide variety of props that sitters could choose from. Mary seems to be posed with a bouquet of flowers–possibly dried?–which I don’t recall seeing before.

I was curious who else was photographed on the same day as James Harrison (21 July 1862), so I entered the date in the search field. That yielded 37 sitters, but no one else with the name of Harrison. At any rate, Silvy’s studio was a busy place!

LikeLiked by 2 people

I keep hoping to find James’s wife (my great-great grandmother) on there but she is not on under her maiden name and didn’t marry until 1866 – I think the NPG has only just started adding the day books from that year, so I live in hope! I was interested to see Lafayette feature on your blog as I’m sure I have a portrait by his studio too, buried upstairs somewhere…

LikeLiked by 2 people

Many of Silvy’s sitters are unnamed, or are identified only by their surname. That said, Althea probably didn’t sit for Silvy, as her family wasn’t wealthy.

The Lafayette studio is remarkable for its longevity!

LikeLiked by 1 person